Styles and Trade-offs #

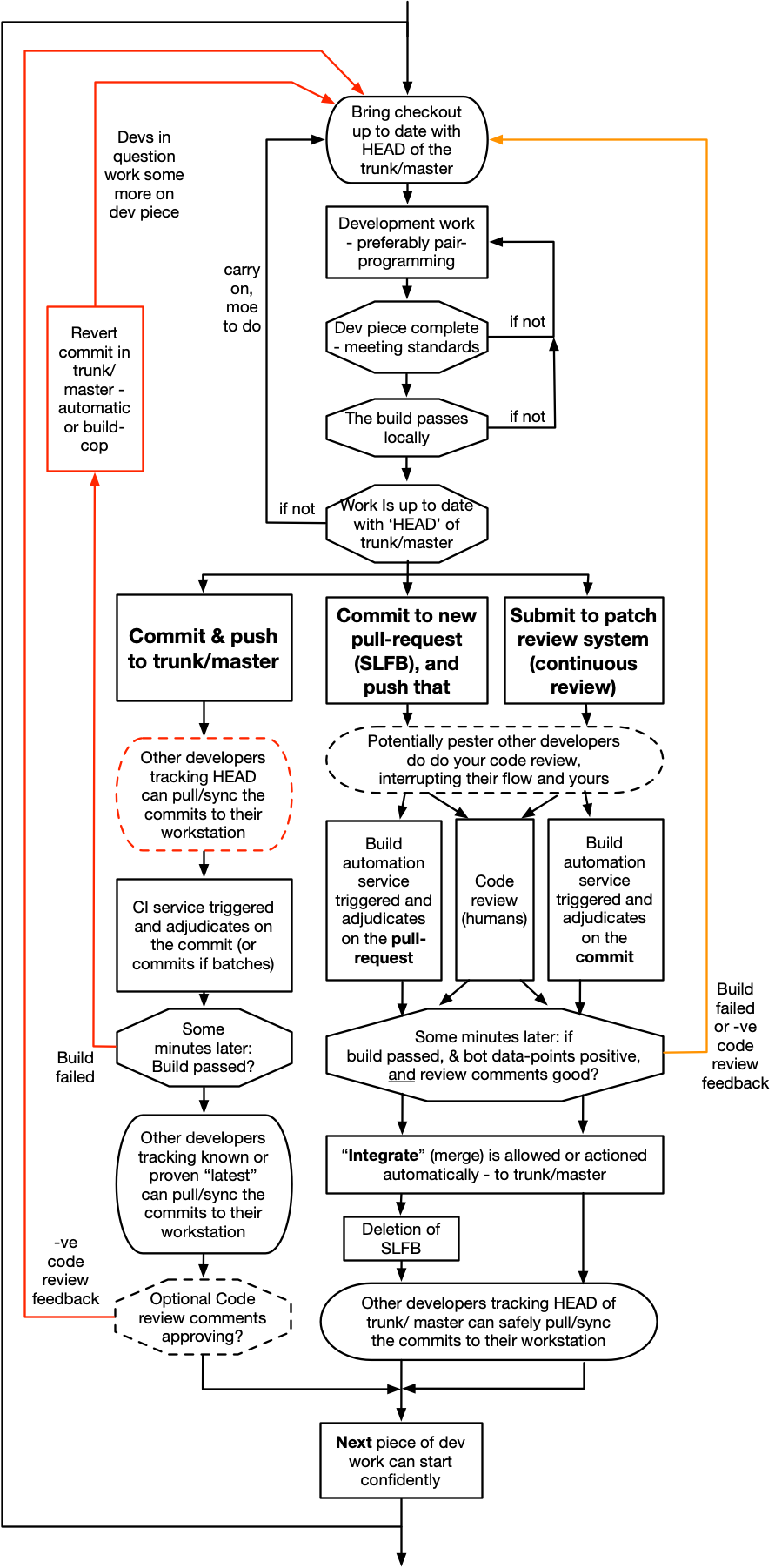

There are broadly three styles of trunk-based development as a daily developer activity. Depending on the number of developers in the team, the release cadence, and the desired rate of commits (assuming story-sizes that support that), you have trade-offs for each of the three:

Committing Straight to the Trunk#

Suitable for active committer counts between 1 and 100, for the same repository

left hand side of the diagram above#

Traditionally Trunk-Based Development meant committing straight to the shared trunk of the VCS in question. And doing so after a bunch of steps that together with the commit we will call integration.

This is a really high throughput way of working, but it relies on developers being extremely sure their commit is not about the break the build. If they do, then a manual or automatic revert gets the trunk back to a good state, and you hope nobody did a git-pull or svn-up to bring that bad commit into their workstation. Or you’ve engineered it so that does not happen - you publish a known-passing latest commit number or hash, and make a wrapper for git-pull (svn-up, etc) to go get that instead of HEAD.

A related challenge is how long “the build” takes to execute by the CI service, versus how frequently the trunk is updated with commits for all the committers that could. This is important because if the build fails (CI), there could be following commits that would pass if it were not for the preceding failing commit. To pick that a part could be a challenge if the commit rate is high enough. Some build-cops lock the trunk at the first sign of a breakage. Best of all is a bot that reverts specific commits that failed the build, but again that is hard science. If your build is 10 seconds (start to finish), and there is one commit every five minutes, then you are in a good position. If your build is five minutes and your team’s commits arrive every ten seconds, then you’re in hell, and should try something else.

See committing straight to the trunk for more info.

Short-Lived Feature Branches#

Suitable for active committer counts between 2 and 1000, for the same repository

center of the diagram above#

Git and Mercurial delivered truly lightweight branching capability. What that meant was that branches could be very quickly created and receive commits that are momentarily divergent from trunk or main (in our case) and then be merged back later when ready. Then finally, and crucially, the branch that facilitated that short-lived divergence could be deleted quickly leaving only the the commits added to the effective lined of commits culminating in HEAD for trunk or main. In that regard it is identically to the patch review way of working for trunk based development. That was all just a small data point for Git/Mercurial usage, until GitHub launches and had pull-requests as a feature from launch. Built in to that was a code review tool. This is a very compelling setup for unsolicited code contributions - making SourceForce and the Apache Software Foundation appear ancient, by comparison.

Teams can form around the GitHub pull-request workflow, and still do Trunk-Based Development. What you get (if you’ve attached build automation too), is a trunk or main that’s never broken (or 1/1000th as likely to). The trade-off is that you have to persuade co-workers to review your commit(s) in a time frame that suits you. There’s a risk that you’d end up putting more commits in the pull-request than the straight-to-trunk experts would do. But you don’t have to. You could stream four separate facilitating commits all the way into the trunk, and later the fifth that would complete/activate the feature you were trying to implement as specified by the Agile story/card. Not only is there a risk of more-commits than you’d do if you could push directly, there’s a risk of taking more time too. If your average story size should be one day, a slow-review and slow-build reality for the pull-request way, might push you into multi-day stories/cards, and from that be doing the opposite of getting to continuous delivery.

See short-lived feature branches for more info.

Coupled “Patch Review” System#

Suitable for active committer counts between 2 and 40,000, for the same repository

“We do Trunk-Based Development” - Googler Rachel Potvin - @Scale keynote, Sept 2015 (14 mins in):

right hand side of the diagram above#

Perhaps before others in the early 2000’s, Google hit a ceiling on how many developers could commit to a trunk in a monorepo, without tripping each other up. That would be build-breakages mostly, but also commits that wouldn’t be up to coding standards even if the build still passed. Say Google managed to get 1000 developers and QA automators working in with commits straight into the trunk, before deciding that something needed to gate that. What resulted was a patch review system that would ultimately be called Mondrian and be announced to the world in 2006 at a tech talk in Mountain View. This was a system that Google had written to augment Perforce (the VCS they used up to 2012), to provide a place where code could be reviewed per-commit, and also build-automation results could be collated.

Today, patch review systems include Gerrit, Rietveld and Phabricator. The latter by Facebook, and the first two with Googler involvement. These are not branches of course, they are held outside source-control in a relational schema. Their reason for existence is to marshal pending changes, before they arrive in trunk/main and to guarantee they are good to be integrated.

The Importance of a Local build#

In all variants of Trunk-Based Development teams run the full build locally (compile, unit tests, a range of integration tests) and see that it pass, before declaring ‘done’ and committing/pushing the work to the eyes of teammates and bots (code review / pull-request), or directly into trunk/main. They do not at all use build automation as a crutch in order to determine whether their commit(s) were good or bad. Instead they determine that themselves on their dev workstation or containers/VMs that are dedicated to them, and do so before pushing something towards code review and bot scrutiny. As mentioned above keeping this build fast is very important, and not having a fast build is one of the key drivers to other branching models and repo sharding. Indeed it is one of the key drivers to slower release cadences too.

Choosing a style#

While it is best to keep developer teams small, sometime there are business pressures to grow a dev team in order to do more in parallel. Indeed, with monorepo configurations that could be more dev teams sharing one repo, even if they have their own release cadences, and separate team organization to other teams.

If Google had (say) 1000 committers doing “straight to the trunk” for a single monorepo back in 2002, should you? No, not since alternates are now possible. If Google had the Mondrian of 2006 back in 2002, they would have moved to that way of working sooner.

What is the cut off point today? Super skilled XP era developers who are in charge of dev teams and can train developers in the applicable way of working, might say the cut-off is now 100 committers. People who’ve only ever know the pull-request way of working may suggest 10 committers is the cut off point. They may even make a case for 2 committers. You could well be in a world where quorums naturally form within teams, leading to new development directions to be effectively set. In Google, it was employee #1 Craig Silverstein who initially held Google to the monorepo and trunk-based development. And he perhaps did that despite quorums forming and group wishes to do something else.

A list of trade-offs are:

- Whether your build technology needs to build ‘everything’ for every commit. Google’s Blaze (Bazel in opensource-land) does not.

- Whether your source-control system has a push/pull bottleneck and whether you’ve reached that with all the committers in one repo

- The median build duration, versus that commit rate.

- How often your build-automation infra falls behind the commits/pull-requests that need to be compiled/tested.

- Whether your developers can avoid using the automated builds as a crutch

- Whether follow-up commits are a workable way of addressing things that need improvements

- Whether the developers are good at separating refactoring commits from functional commits, and indeed “baby commits” generally.

- Whether your team can handle code-review feedback after commit/push to trunk/main or not